Chapter 5

Additional Data Collection Methods

By Dyanna Gregory

Not all types of information are easily gathered using surveys. Surveys are self-report tools that take place at a single point in time, so exact measurements, external impressions of reactions, and data about things that happen over time can be difficult to capture. Nevertheless, these are important pieces of information that you may need, so let’s discuss a few of the other data collection tools you can use to better collect these types of data.

| Method | Good if: |

|---|---|

| Direct measurement | Values need to be exact; Information likely to be biased if self-reported |

| Focus Groups | Don’t know exactly what you want to ask yet; Interested in full spectrum of reactions or multiple topics; Interested in group dynamic; Interested in decision process |

| Observation | What you’re measuring is easily and publicly observable; You want to make notes about participant behavior |

| Examination of existing documents | The data you are interested in are already recorded elsewhere (e.g. on receipts, logs of web traffic, etc.) |

| Diaries | Need to track variables over time; Information likely to be biased if recalled later |

Direct Measurement

There are some variables that should be measured rather than surveyed if you’re trying to obtain an exact, correct statistic. Many medical variables, for example, are difficult if not impossible to gather accurately using a survey. Let’s say you need to collect data on participants’ weight at the beginning of a study. There are a few common reasons someone might report an inaccurate number.

- Lack of information: they didn’t actually know how much they weighed when asked

- Social expectation: they felt there was a “correct” answer they were supposed to give

- Ease of response: they knew about how much they weighed but didn’t think the exact answer was needed; “I’m about 170 lbs, so I’ll say that.”

Whether your data need to be exact depends on how you’re using the the information. If you’re not concerned about having a precise measurement and an estimate will work, then a survey might be fine as long as it asks something people will be able to reasonably estimate. If you have a variable is likely to be incorrectly self-reported and it is important that these data are current and accurate, direct measurement should be used instead of a survey.

In direct measurement, you use an appropriate device to measure the variable and then record the value in the dataset. This is often done for health-related variables that a person wouldn’t be able to “just know.” The measurements are usually captured on forms and the data is transferred from the forms into the dataset.

It is important for your forms to be clear about how you want the measurement to be recorded. You should indicate the preferred units and the precision you want the measurement captured with. One of the easiest ways to communicate this is by allotting a specific number of boxes so the person taking the measurement knows how many digits you want recorded.

The image below shows an example for how we might set up a form for capturing adult weight. Here, we want the measurement in pounds, and we want the number recorded to two digits after the decimal place.

When relevant, include a place to record what device was used to take the measurement.

Focus Groups

Sometimes it’s helpful to watch people while they’re responding to your questions, see their thought processes, and observe them interacting with others. You may also have a wider variety of topics you would like to cover than would make sense for a survey or you might not be sure exactly what questions need to be asked yet. Focus groups can help in all these situations.

A basic focus group works a lot like a facilitated book club meeting. A small group of people (usually 6 to 12 individuals) is gathered to discuss their thoughts on a specific topic, and this discussion is led by a trained moderator. The moderator asks a variety of questions in order to get more in-depth opinions than a survey would answer alone. Focus groups often have more flexibility than surveys in that the questions are not entirely pre-determined. The moderator has more freedom to explore the answers the respondents provide and formulate new questions based on those responses. Additionally, since participants are in a group, the answers one person gives may cause another to think of answers they might not have otherwise.

However, both the group setting and the presence of the moderator can create bias in participant responses. It is important to keep this in mind when reviewing and analyzing focus group data.

Observation

Sometimes the data you need to collect are a matter of observation. Let’s go back to Fictionals Ice Cream Parlour for a moment. You recently purchased new furniture for the store, and you’re considering a couple of different layouts for it. You want to see which layout seems to work best for customer flow, so you set up the furniture one way for a few days and record your personal observations about customer movement within the shop. Then you switch the furniture to the other layout and again record what you notice. These data can help you figure out what other questions you might want to ask or what other data you need before making your decision.

You can use observation in this way to gain insight into naturalistic behavior. This can be especially useful if your subjects of interest are not human and can’t answer survey questions: scientists rely on observation as a data collection technique all the time!

One of the major shortcomings of this method is that the presence of an observer changes an observation. Every person sees an event from their own perspective, and their report of that event is influenced by that perspective. You can decrease this bias by having several observers so that the data gathered represents multiple viewpoints.

Examination of Existing Documents

In some cases, the data that you need already exist as parts of other documents and your data collection is really a matter of getting all of that information into one place.

As the manager of Fictionals Ice Cream Parlour, you want to take a look back at your sales for the last six months to see if your recently-added menu items have been profitable. This information is already available to you through your receipts or POS software data. You just have to get it set up in a way that allows you to easily work with and analyze it.

Other existing documents that are frequently used to compile information include books, newspapers, web traffic logs, and webpages. There are also entire datasets that are available for use. These are covered in more detail in the chapter on Finding External Data.

When you’re using other documents as the main source of your data, you should first set up a data collection plan, much the way that you design a survey. The plan should detail what pieces of data you’re looking for, the level of measurement you want to capture them at, the time frame you need (e.g. do you only want data from the last 6 months? the last 12?), and how much data you need (e.g. do you want to look at all the receipts or just a sample of them?).

If any of the sources are ones that you don’t own, make sure to properly cite them. It’s important to credit others’ work, and it’s also important to be able to support your research if anyone challenges your information later on.

Diaries

Diary forms can be useful if you’re collecting data from people about things that are happening over extended periods of time. They are particularly helpful if you them to record a lot of details that could easily be misremembered or forgotten.

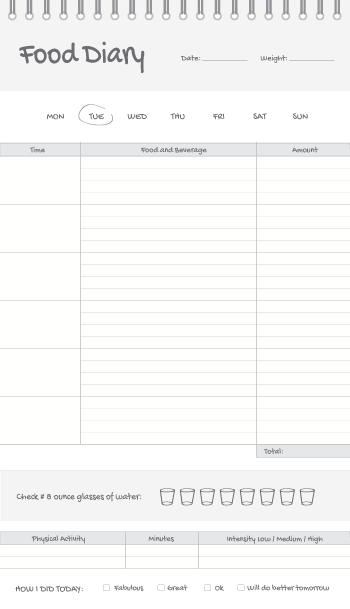

You might have seen something similar to this before:

Diary forms are often used for tracking things like meals, medications, or exercise but can be used for anything you want to record over time. They can be paper forms or computerized, but should follow the same design principles as surveys. Fields should be well-labelled and the instructions should be very clear about how (and how often) the diary should be completed.

Using Multiple Collection Methods

When you’re considering a project as a whole, it is possible that not all the research questions you’re trying to address can be answered using data collected from just one of the methods discussed so far. You may find that your survey will need to be supplemented with some direct measurements, or you may need to have your focus group participants complete diary forms.

Just as you can benefit from a combination of survey types, you can also benefit from incorporating multiple types of data collection if the data you need would most appropriately be gathered in different ways. Consider what approaches make the most sense for the data you need, and then select the best choices that are practical within your budgetary and time constraints.